What eight European initiatives taught me about knowledge and action

Written by: Karen Soacha-Godoy

Next May 18th, I’ll sit at a round table in Barcelona to discuss three years of mentoring through the IMPETUS Accelerator program. It feels like the right time to reflect on what these eight initiatives across six countries have taught me about citizen science, community mobilisation, and the messy business of creating change.

Let me start with what surprised me. When I began in 2022, my experience was mostly in biodiversity mapping and monitoring in Colombia and Catalunya. Then I met these European teams working on everything from marine pollution to archaeological conservation, from mobility accessibility to climate adaptation. The geographic spread was vast – Italy, Poland, Spain, Turkey, UK, Portugal – but they all shared something: using science for community and environmental benefit, solving real problems.

The initiatives that shaped my understanding

In 2023, Chiara and her team from SeaPacs in Anzio, Italy, showed me what actionable citizen science looks like. They weren’t just studying marine pollution – they were mobilising fishermen, sailors, students, and developing DIY devices to sample microplastics. This wasn’t research happening to a community; it was research emerging from it. They were proposing immediate actions during the development of the project – the results obtained with the fishermen’s cooperative in cleaning up the harbour are a clear example of this approach.

That same year, See Science Save Seashores in Poland had students mapping plastic and seaweed along the Baltic coast, work that would influence education curricula. Meanwhile, Accessible Kadıköy in Istanbul invited citizens to document inaccessible sidewalks through an app, turning everyday frustration into data for urban improvement.

By 2024, my understanding deepened. Maria Vicente’s WellBeing Blitz in Portugal completely shifted my thinking – instead of mapping biodiversity in 24-hour bioblitzes, they were mapping food availability around schools, tracking Mediterranean diet access. It was innovative, unexpected, and perfectly logical once you saw it in action.

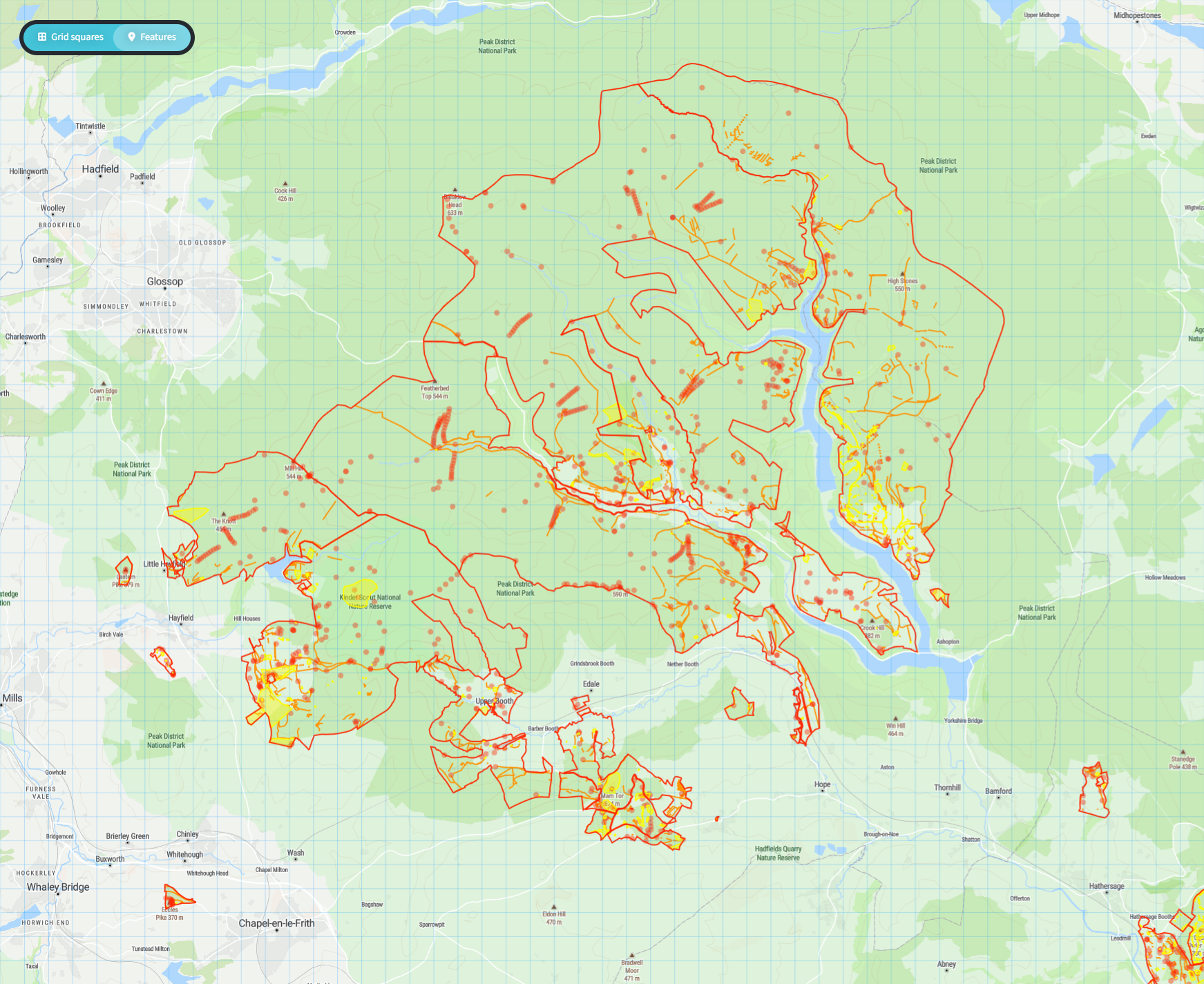

Then came Deep Time in the UK, where Brendon and his team from DigVentures had built a platform for citizens to detect archaeological sites through satellite imagery. Our conversations about data governance, data cooperatives, and ethical use of data were intellectual sparks flying – this was my area of expertise finding new applications.

This year brought three more perspectives. HeatWatchers in Barcelona involves students measuring temperatures in their homes and co-creating heat solutions for vulnerable populations. Of course, it’s exciting working with initiatives in Catalunya, my home nowadays. Wildin in Granada works with neurodiverse communities to understand rabbit conflicts in vineyards – watching them design accessible materials and activities enriched everyone involved. And Shifting Sands in Fiumicino, where local organisations, researchers, women, gather bathymetry data to document the ecological impact of a proposed cruise port, showing how citizen science can support environmental activism.

When different knowledges met

Each initiative brought technical knowledge I couldn’t have imagined – bathymetry, archaeology, marine microbiomes, heat vulnerability mapping. Listening to them was like diving into worlds of experience, conflicts, and methodologies. But more importantly, they showed me how citizen science creates a meeting space where different types of knowledge converge.

Scientists, activists, educators, students, fishermen, sailors, neurodiverse participants – all bringing their expertise to solve problems that matter to their communities. These weren’t the usual suspects in scientific research. They were people whose knowledge often goes unrecognised, now central to creating understanding and change.

This diversity challenged me constantly. In my area of data governance and ethics, implementing best practices isn’t straightforward. Most initiatives involved participants throughout the data cycle – from collecting to understanding to seeing impact. But distributing decision-making power over data beyond the research team? That requires maturity and intentional design that we’re still figuring out. Open data was always on the table. Privacy protection always in conversation. Gender perspective also in the radar. But the deeper questions about data cooperatives and distributed governance remain works in progress.

Rethinking support and sustainability

The name “accelerator” never quite fit for me. These initiatives didn’t need acceleration – they needed nurturing. It felt more like tending plants that were struggling to grow, not because they were weak, but because they were part of complex ecosystems. Sometimes you add nutrients, sometimes you remove obstacles, sometimes you just create space to keep growing. Many of these teams were already robust forests.

IMPETUS provided training in storytelling, policy advocacy, impact assessment, data ethics – all the dimensions a citizen science initiative needs to address with usually limited funding. The program offered training sessions plus peer-learning aperitives with the wider community.

But as IMPETUS ends, I wonder about what comes next. These aren’t single-point projects but long-term initiatives where IMPETUS injected vitamins to keep going. They need sustained support, a rethink how to provide periodic nurturing. They’re demonstrating that citizen science can be flexible, adaptable, and create both scientific knowledge and immediate social impact.

The deeper lessons

What strikes me most is how these initiatives operate on multiple timescales simultaneously. Some, like See Science, work on long-term educational change. Others respond to immediate environmental conflicts, like Shifting Sands documenting port construction impacts. All of them show that citizen science isn’t just about producing data – it’s about transforming how we understand problems and who gets to be part of solving them.

The tangible outcomes vary wildly, and that’s the point. From SeaPacs’ harbour cleaning actions to HeatWatchers’ cooling solutions for vulnerable populations, from influencing curricula to preventing infrastructure damage – each initiative creates change that makes sense in its context.

Working across such diversity – marine pollution, agricultural conflicts, diet sustainability, archaeological conservation, mobility accessibility, climate change – taught me that citizen science’s real power lies in its adaptability. It can be whatever a community needs it to be, as long as it maintains scientific rigor and social purpose.

Looking forward

The round table in Barcelona will close this mentoring phase, but these initiatives continue. They’ve taught me that knowledge and action aren’t separate things in citizen science – they’re intertwined, each feeding the other.

As I prepare for Barcelona, I think about what we owe these teams. Not just funding, though that’s critical. Not just training, though that helps. They need the recognition that they’re creating a different kind of science – one that doesn’t sacrifice rigor for relevance or expertise for inclusion. They’re showing us that the choice between scientific excellence and social impact is a false one.

These eight initiatives across six countries have given me countless lessons. They deserve our sustained support, our attention, and our willingness to learn from what they’re building. Because they’re not just collecting data or solving local problems – they’re reimagining what science can be when communities lead the way.